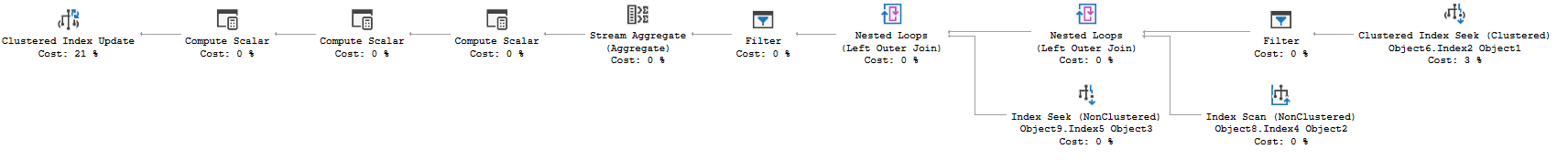

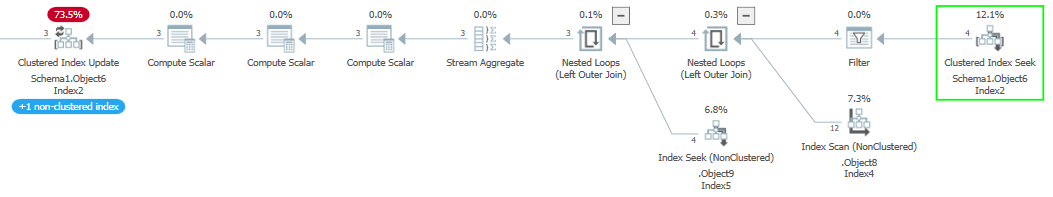

I encountered something recently I’d never encountered, so I had to share. I was making another change to a procedure I’ve been tuning recently. The idea was to alter the UPDATE statements to skip rows unless they are making real changes. The activity here is being driven by customer activity, and that sometimes leads to them setting the same value repeatedly. Difficult to know how often we update a row to the same value, but we think it could be significant. So, we added a clause to the UPDATE so we’ll only update if ‘old_value <> new_value’. The actual update operator is the most expensive part of the statement, but  Simple enough so far. The scan is against a memory optimized table variable, and the filter to the left our our seeks and scans check for a change to our value. Nothing left but to update the index and…

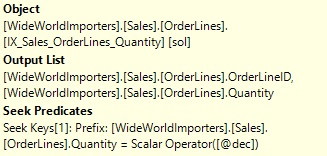

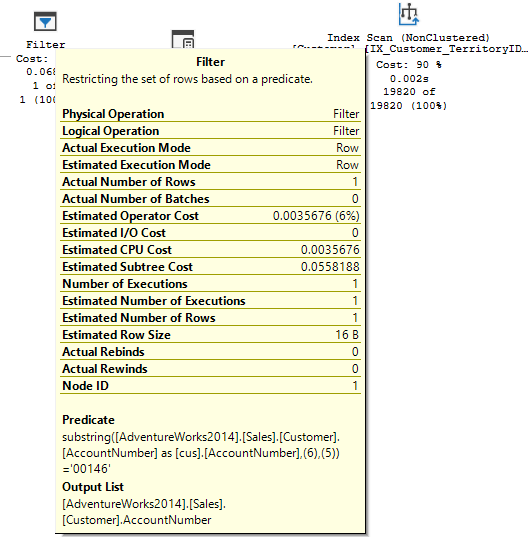

Simple enough so far. The scan is against a memory optimized table variable, and the filter to the left our our seeks and scans check for a change to our value. Nothing left but to update the index and…

Curve Ball

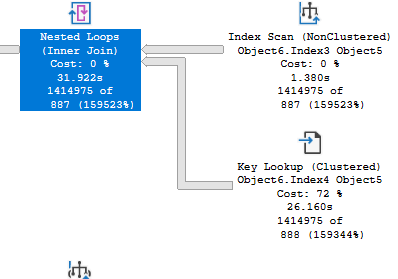

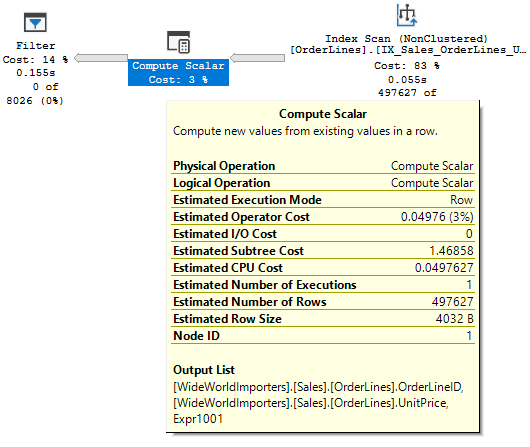

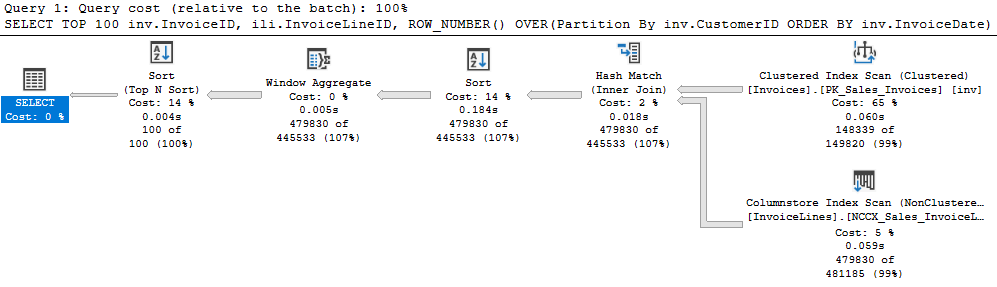

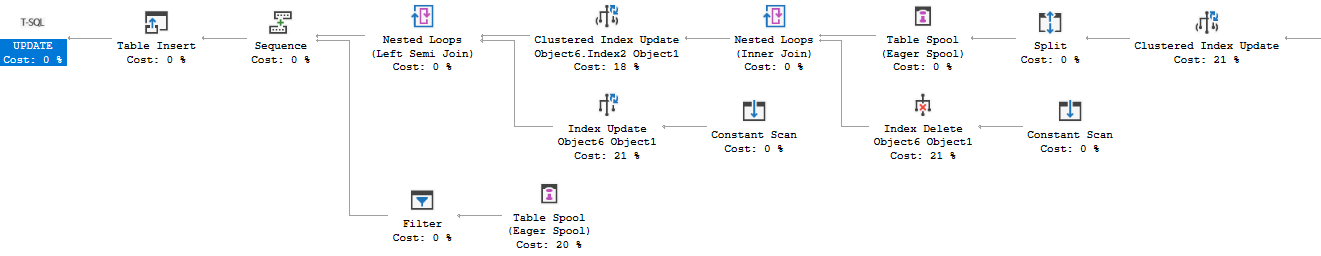

Wait, what’s all this? We have a Split operator after our Clustered Index Update. SQL Server does sometime turn an UPDATE statement into effectively a DELETE and INSERT if the row needs to move, but this seems a bit much. We have a total of 4 index update/delete operators now, and they aren’t cheap. My very simple addition to the WHERE clause actually caused a small increase in duration, and a big jump in CPU. So what’s going on?

Wait, what’s all this? We have a Split operator after our Clustered Index Update. SQL Server does sometime turn an UPDATE statement into effectively a DELETE and INSERT if the row needs to move, but this seems a bit much. We have a total of 4 index update/delete operators now, and they aren’t cheap. My very simple addition to the WHERE clause actually caused a small increase in duration, and a big jump in CPU. So what’s going on?

UPDATE Object1

SET

Column1 = CASE

WHEN Variable1 = ? THEN Object2.Column1

WHEN Variable1 = ? THEN Object1.Column1 + Object2.Column1

END,

Column4 = GETUTCDATE()

FULL OUTER JOIN Variable5 dcqt

ON Object1.Column9 = Variable2

AND Object1.Column10 = Variable3

AND Object1.Column6 = CASE WHEN Variable6 = ? AND Object2.Column2 >= ? THEN ? ELSE Object2.Column2 END

LEFT JOIN Variable7 oq

ON Object1.Column6 = Object3.Column6

WHERE

Object1.Column10 = Variable3

AND Object1.Column9 = Variable2

AND Object1.Column2 >= ?

AND Variable8 < ?

AND Object1.Column1 <> CASE

WHEN Variable1 = ? THEN Object2.Column1

WHEN Variable1 = ? THEN Object1.Column1 + Object2.Column1

END

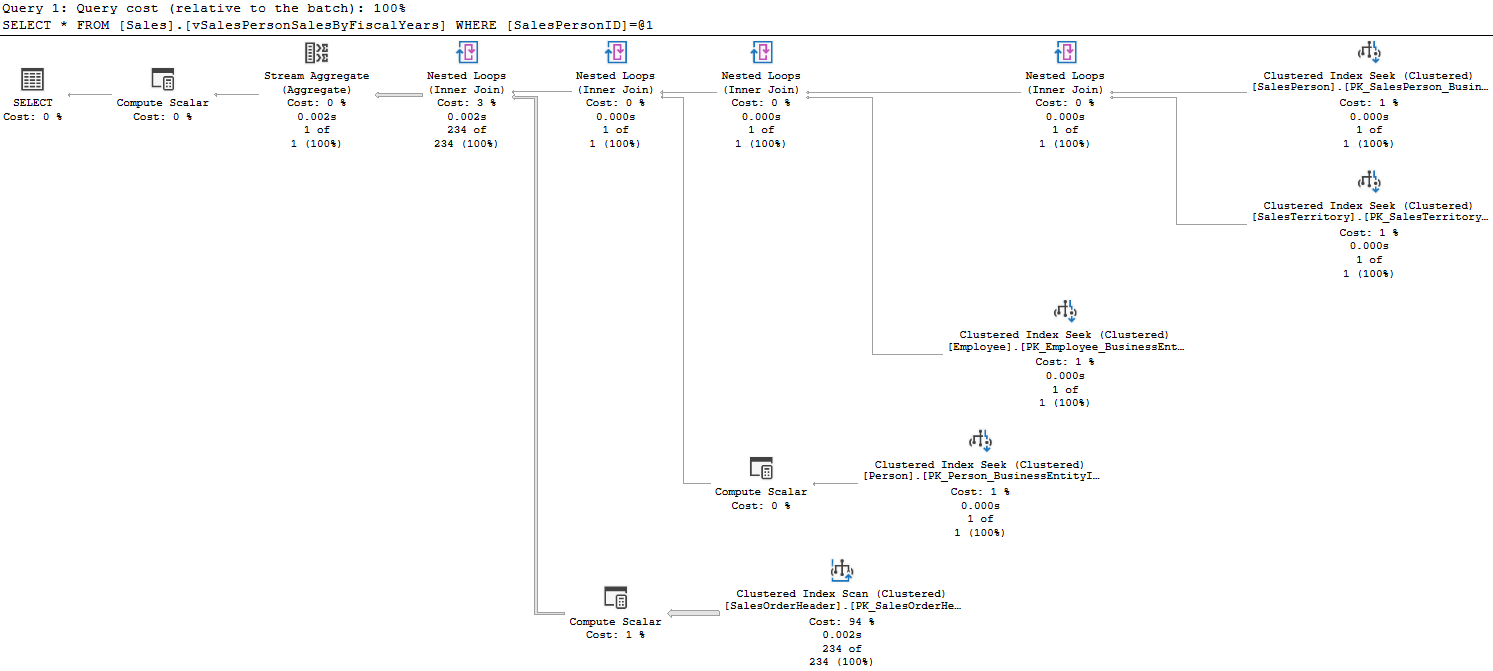

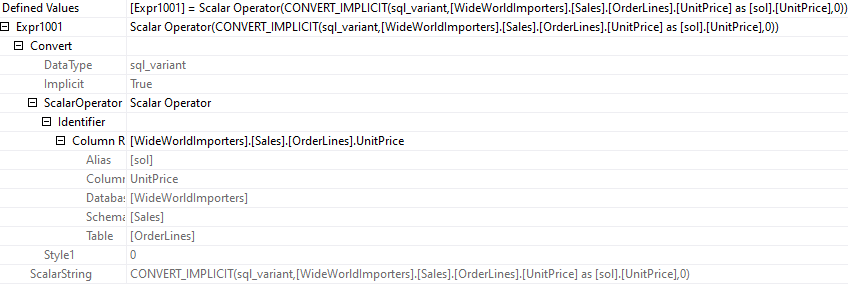

So, we’re updating Column1 to the result of a CASE statement, and the last part of our WHERE clause compares Column1 to the same CASE. And the CPU for this statement just doubled? I happened to jog this by the superlative Kevin Feasel, who suggested this was the Halloween Problem.

The Halloween Problem

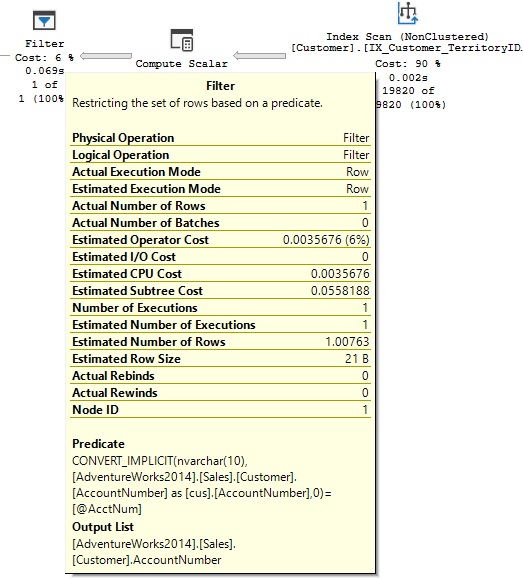

The Halloween Problem is a well documented issue, and it affects other database systems, not just SQL Server. The issue was originally seen by IBM engineers using an UPDATE to set a value that was also in their WHERE clause. So, database systems include protections for the Halloween Problem where necessary in DML statements, and SQL Server decided it needed to protect this query. And our query matches the pattern for this issue; we’re filtering on a field while we are updating it. All DML statements can run afoul of this issue, and there are examples for all in this really excellent series of posts by Paul White.

An Unlikely Ally

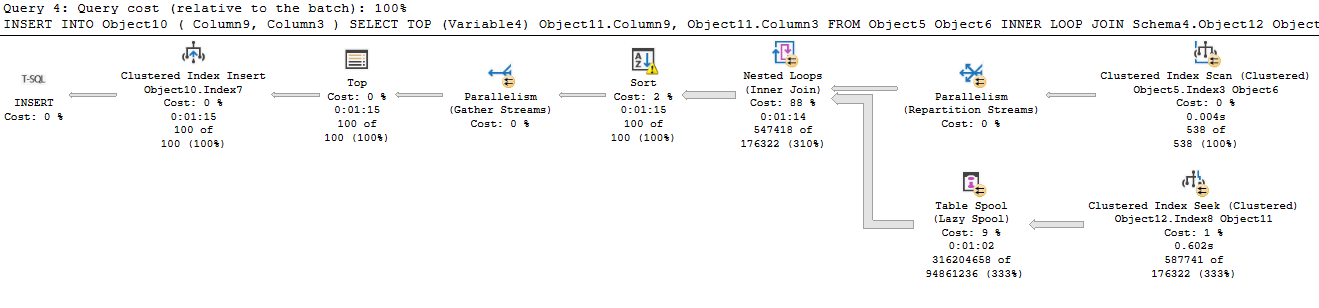

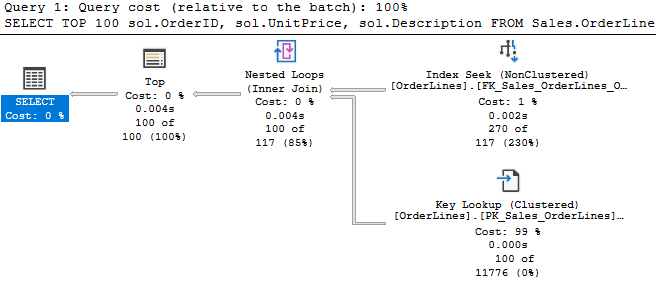

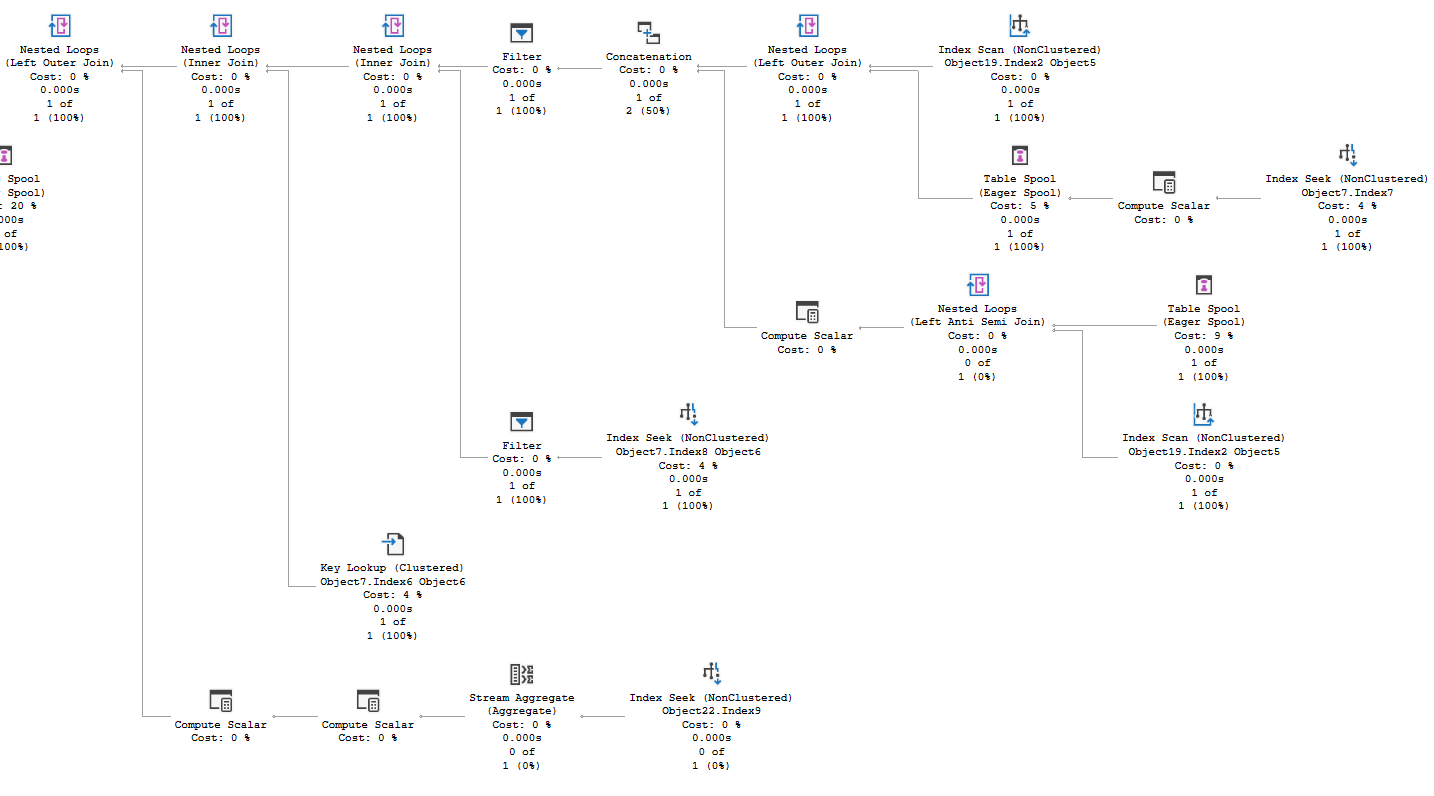

The protection SQL Server employs ultimately comes down to interrupting the normal flow of rows from operators up the plan. We actually need a blocking operator! A blocking operator would cause all the rows coming from the query against our primary table to pool in that operator. We’ll have a list of all relevant rows in one place, and they can be passed on to operators above without continuing the index seek against our table; possibly seeing the same row a second time. Eager spools\table spools are frequently used for this purpose, and SQL Server used an eager spool to provide Halloween protection in my case. A sort would also do, and we could design this query to sort the results of querying the table. If our query already employed a blocking operation to interrupt the flow, SQL Server would not need to introduce more operations to protect against the Halloween Problem. In my case, I definitely don’t want it spooling and creating three more expensive index operations. My idea for rewriting this goes a step farther.

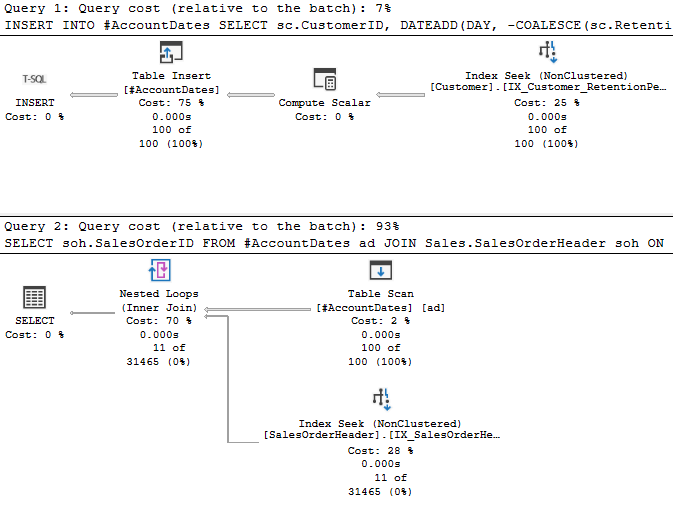

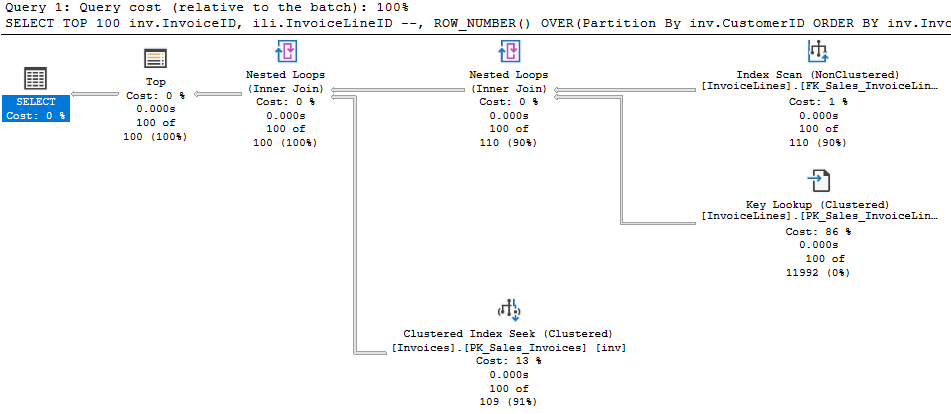

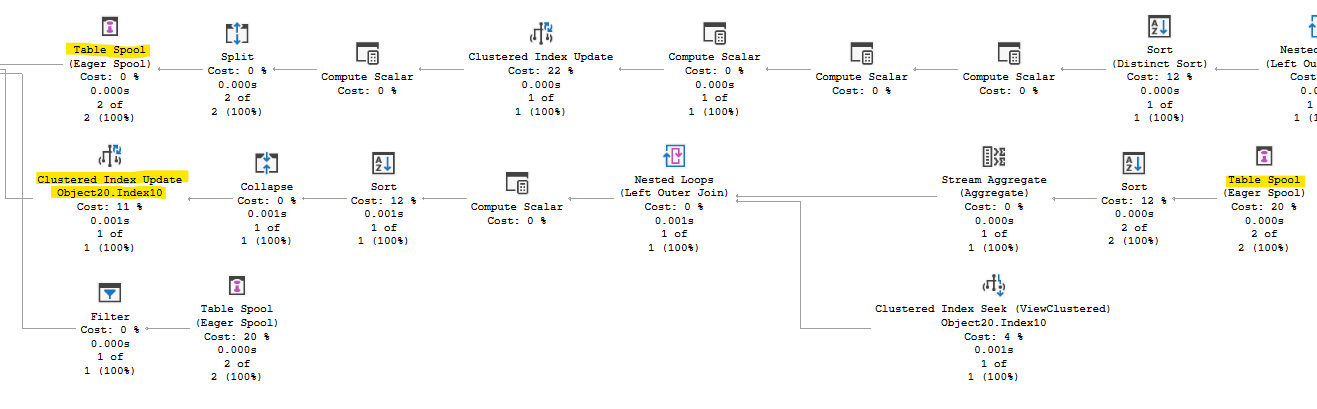

A Two Table Solution

If we queried the data from our base table into a temp table, we could then update the base table without querying that same table on the same column, tripping over a pumpkin in the process. My procedure is already using memory optimized table variables, because this proc runs so frequently that temp tables cause contention in tempdb (described here). So in this instance, I’ll actually query this data into another motv. I can also use the data I stash in my motv to decide if any rows I intended to update don’t exist yet. I’ll INSERT those later, only if needed.

Bonus

Now, the whole point of the original change was to reduce work when we update a field to be equal to its current contents. In my motv, I’m going to have the old and new value for the field. It would be simplicity itself to put my UPDATE in a conditional, so that we only run the UPDATE if at least one row in my motv is making an actual change to the field. So instead of just reducing the cost of our update operators, we’ll skip the entire UPDATE statement frequently, for only the cost of one SELECT and a write to our motv.

Results

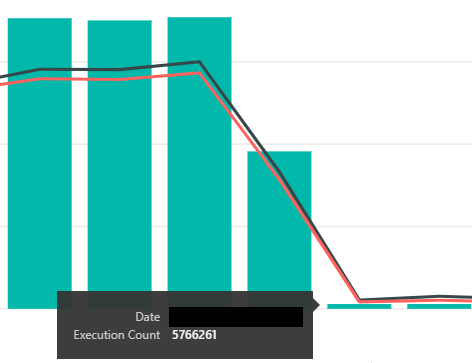

Stunning. The new logic causes this proc to skip the UPDATE statements entirely over 96% of the time. Even given that we are running a query to populate the memory optimized table variable (which is taking <100 microseconds) and running an IF EXISTS query against that motv (which takes 10-20 microseconds), we’re spending 98% less time doing the new logic than the original UPDATE statement. When I started reviewing the procedure several months ago, it took 3.1 milliseconds on average. I’ve tried several other changes in isolation, some effective, some not. The procedure is now down to 320 microseconds; an almost 90% reduction overall after a 71% drop from this change. I have some other ideas for tweaks to this proc, but honestly, there’s very little left to gain with this process. Time to find a new target. If you liked this post, please follow me on twitter or contact me if you have questions.

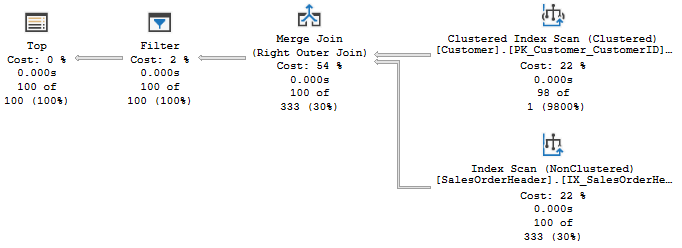

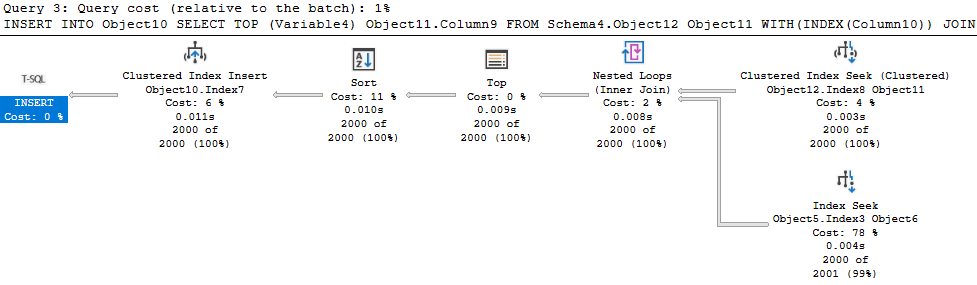

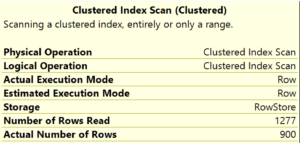

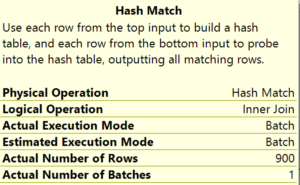

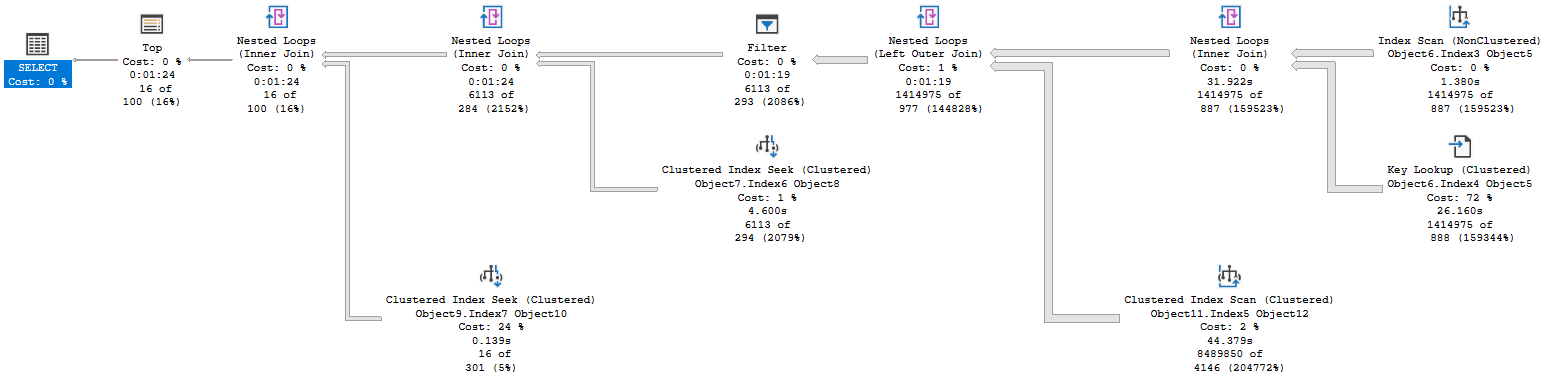

We’re scanning and returning 1.4 million rows from the first table, doing a key lookup on all of them. We scan another table to look up the retention period for the related account, as this database has information from multiple accounts, and return 8.4 million rows there. We join two massive record sets, then have a filter operator that gets us down to a more reasonable size.

We’re scanning and returning 1.4 million rows from the first table, doing a key lookup on all of them. We scan another table to look up the retention period for the related account, as this database has information from multiple accounts, and return 8.4 million rows there. We join two massive record sets, then have a filter operator that gets us down to a more reasonable size.